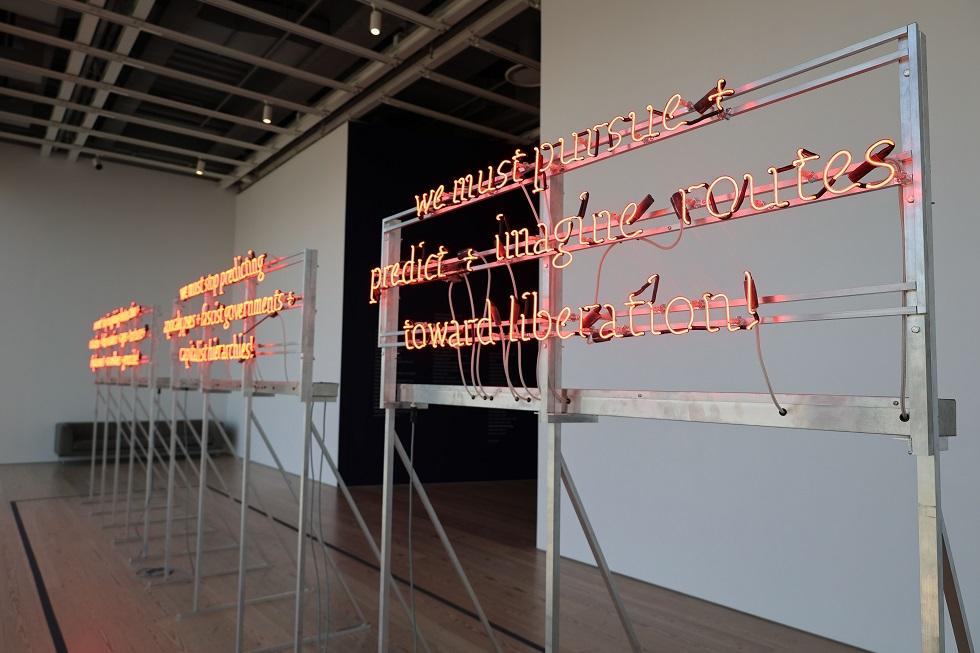

Titled “we must stop imagining apocalypse / genocide + we must imagine liberation,” the Diné artist’s new installation joins the works of some 70 other artists and collectives in the 81st edition of the exhibition, which surveys early-career American artists — and has often been a flashpoint for politics and protests.

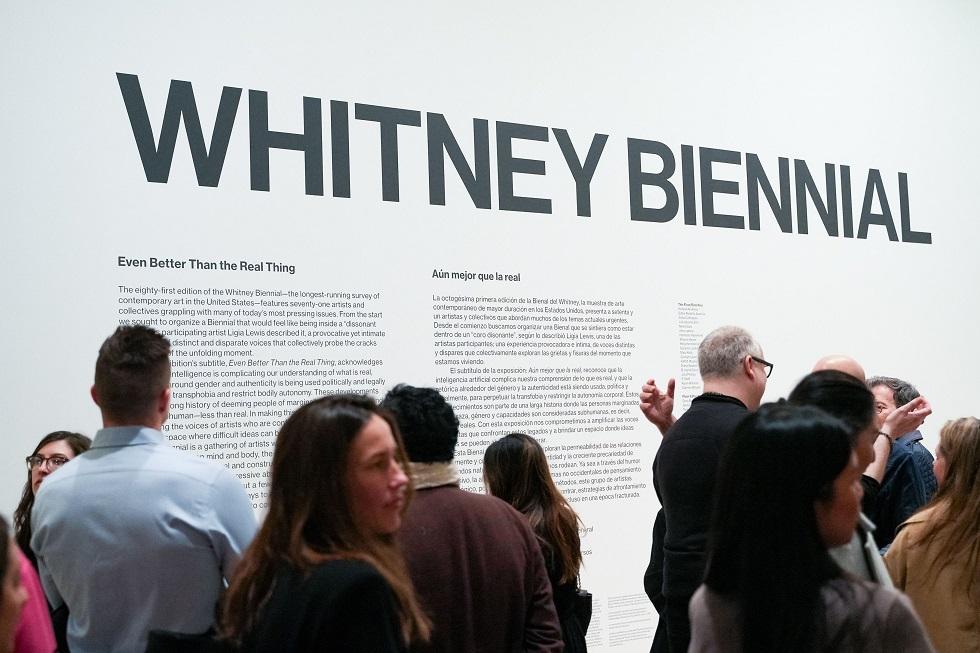

Over email, a Whitney spokesperson confirmed to CNN that the museum “did not know of this subtle detail when the work was installed.” Publicly, it came to light by journalists reporting for Artnet News and The New York Times after the exhibition, titled “Even Better Than the Real Thing,” opened for early previews. (The Biennial will be open to the public as of today.)

DinéYazhi´ explained in a phone call with CNN that the installation “became an opportunity to have a commentary on current world events and do so in a way that was respectful to people’s humanity and dignity.”

Calls for a ceasefire and an independent Palestinian state have increased in recent months, as Israel’s war on Hamas has killed more than 31,000 people in Gaza, according to the territory’s Ministry of Health, and displaced at least 1.7 million since October. This follows the Hamas-led attack in southern Israel that killed 1,200 people, according to Israeli authorities.

To DinéYazhi´, “Free Palestine” is a call “for a permanent ceasefire and an end to occupation, genocide, forced migrations of Palestinian peoples and the right of self-determination for Palestinian peoples,” the artist explained.

“It asks us to consider what healing and building future societies could look like if we were all liberated from disharmonic and divisive political systems, police states, and nation states,” they added.

The artist’s poem reflects on these wider implications, as well as their own history and experiences as an Indigenous person in North America. It reflects on Indigenous resistance and pays tribute to the artist’s friend, the Diné musician and activist Klee Benally, who died in January. And the hidden message is far from the only embedded layer in the neon sign.

“It’s a continuation of the work that I have been involved in, speaking about a lot of issues that affect Indigenous communities,” DinéYazhi´said.

Picturing a way forward

The poem on which the neon sign was based, which was written by the artist around 2019, eschews religious or cultural fascination with predicting destruction and oppression, and calls instead to imagine liberation.

“I was thinking about sci-fi… and Euro-Christian ideas of apocalypse and world-ending, and trying to put that in line with Indigenous ways of viewing the world and Indigenous creation stories,” DinéYazhi´ explained. “And just always seeing conflict come up.”

The use of neon — fabricated in collaboration with the New York-based studio Lite Bright Neon — speaks brightly but subtly to a range of interconnected references made by the artist. One is the ubiquity of neon signage along Route 66 in New Mexico (where DinéYazhi´ grew up) advertising “Indian jewelry” for sale, but often in stores run by people without any Indigenous ancestry, DinéYazhi´said.

And, while this text at the Whitney glows red, they’ve also used vivid yellow neon in the past: At the Honolulu Biennial in 2019, for example, to speak to what DinéYazhi´ describes as the exploitative history of uranium extraction in the country. In the mid-1940s, the US government began mining tens of millions of tons of the yellow ore from Navajo lands to create atomic bombs, around the same time as Indigenous code-talkers (including DinéYazhi´’s grandfather) — whose languages were co-opted for clandestine communications — were coming home from World War II.

“One of the reasons why the US armed forces used the Navajo language was because it was mostly spoken within the reservation, and it wasn’t in written form,” they said. “And so I just had this really unsettling feeling, realizing that my traditional language — which I don’t speak — was translated, and is embedded into a history of colonial conquest and warfare.”

Seeing beneath the surface

Showing at the Whitney at all was a complicated decision for DinéYazhi´, who found it “affirming” to their practice as an artist but is critical of the museum as a “settler colonial institution” in New York City, which was formerly the land of the Lenape people, they explained.

And though DinéYazhi´ found the curatorial team at the Whitney supportive, they said, they were wary nonetheless after a recent incident. One of their artworks, a banner proclaiming “Defund the Police / Decolonize the Street,” was removed, without warning, from display at the Chehalem Cultural Center in Oregon after the opening of an exhibition there last August, with the organizers citing safety concerns. (The center has since publicly apologized.)

Ultimately, DinéYazhi´ chose to be hopeful about the outcome of their decision to include the message without the museum’s knowledge. “As much as I was concerned about what the larger response would be, I also felt that (the Whitney curators) were supportive and understanding of the artistic voice,” they said.

The Whitney has said that they will not remove the installation, stating via a spokesperson that it “has long been a place where contemporary artists address timely matters, and the Whitney is committed to being a space for artists’ conversations.”

For museumgoers who have not yet visited the piece, DinéYazhi´ said they hope that people choose to “really sit” with all of the work in the Biennial.

“I hope they see the complexities of the issues that lie underneath the surface — that they don’t just take a photograph, upload it to social media and move on,” they said. In terms of their own work, those “complexities” extend as far as its position within the museum.

“The sign itself reflects off the windows and back into the institution,” they said. “It looks outward toward the sunset. It looks outward toward so-called American progress into the darkness of the west — (toward) settler colonialism expansion, Manifest Destiny, the Oregon Trail, forced migrations. It’s this really complicated history that we as a country still have not dealt with, and that many people are trying to silence and erase.”

But DinéYazhi´ hopes that people walk away with a renewed sense of hope, and a call to find a better way forward. “There are ideals that are still alive in our communities, that are within our bodies, that are still worth fighting for and nurturing,” they said. “We are still beautiful, powerful beings that can build loving communities, and can care for one another, beyond our differences.”