The 68 million-year-old fossil belongs to an extinct species of bird known as Vegavis iaai that lived at the end of the Cretaceous period, when Tyrannosaurus rex dominated North America and just before a city-size asteroid hit Earth, dooming the dinosaurs to extinction.

Birds that lived among the dinosaurs were barely recognizable when compared with today’s bird species. Many sported bizarre features such as toothed beaks and long, bony tails.

Vegavis, however, would have been ducklike in size and similar ecologically to aquatic bird species such as loons, said Christopher Torres, an assistant professor of biology at the University of the Pacific in California and lead author of the study published Wednesday in the journal Nature.

“So this bird was a foot-propelled pursuit diver. It used its legs to propel itself underwater as it swam, and something that we were able to observe directly from this new skull was it had jaw musculature (that) was associated with snapping its mouth shut underwater in pursuit of fish. And that is a lifestyle that we observe broadly among loons and grebes,” he said.

Paleontologists first described Vegavis 20 years ago, but many were skeptical that it represented a modern or crown bird species. Most modern bird fossils that had been unearthed at that point dated to after the dinosaur-killing asteroid struck off the coast of what’s now Mexico 66 million years ago. Many scientists assumed that modern-looking birds began to evolve after and perhaps in response to the mass extinction.

Previous Vegavis fossil specimens also lacked a complete skull, said study coauthor Patrick O’Connor, a professor of anatomical sciences at Ohio University. Skulls are where the most characteristic features of modern birds, such as a lack of teeth and an enlarged premaxillary bone in the upper beak, can be identified.

The fossil examined in the study, collected during a 2011 expedition by the Antarctic Peninsula Paleontology Project, was found encased in rock that dated back 68.4 to 69.2 million years and displayed modern characteristics, such as a toothless beak, according to the study.

“The new fossil shows Vegavis is undoubtedly a modern bird (something that was challenged in the past) and is an exceptional find preserving a strange and surprising morphology,” said Juan Benito Moreno, a fellow in the department of Earth Sciences at the University of Cambridge and an expert on fossil birds, in an email.

“The new skull of Vegavis shows a very specialized morphology for diving and fish-eating, more so than I would have expected,” added Moreno, who was not involved in the study but was involved in the discovery of the only other known modern bird species from the Cretaceous.

A survivor of mass extinction?

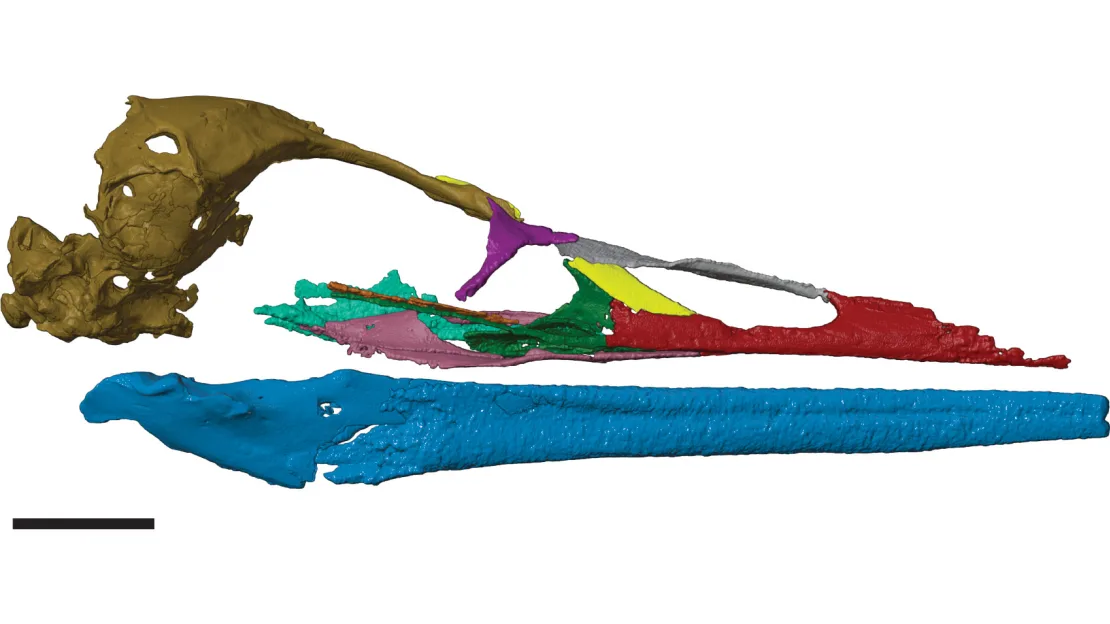

The brain shape revealed by the new fossil, which researchers scanned using computerized tomography to create a three-dimensional reconstruction, was also characteristic of modern birds, according to the study.

Together, these features place Vegavis in the group that includes all modern birds, and the fossil skull represents “the earliest member of this entire radiation that we see around us today, that consists of 11,000 bird species,” O’Connor said.

While Vegavis resembled present-day waterfowl in some ways, other features didn’t fit the mold. For instance, the study noted that the skull preserves traces of a slender, pointed beak powered by enhanced jaw muscles, a feature that is more like diving birds than other known waterfowl.

“Antarctica at 69 million years ago didn’t look like it did today. It was forested. It was a cool, temperate climate based on most of our modeling, and this animal, we recovered it in a marine rock unit so we would envision that it was doing this pursuit diving in a nearshore, marine environment,” O’Connor added.

Torres, who was a postdoctoral fellow studying avian paleontology at Ohio University when he conducted the research, said the discovery of the Vegavis fossil in Antarctica and a fossil of an extinct bird species known as Conflicto antarcticus from a nearby location dating from shortly after dinosaurs’ extinction would allow paleontologists to investigate how some animals survived the cataclysmic event.

“What happens to the survivors? What determines, number one, what a survivor is, and number two, what are the survivors going to look like after one of these catastrophic events?” he said.